On a crisp autumn day in the late ’80s, more than a hundred thousand people made their way towards the college football stadium about four blocks from my childhood home. Given that the town’s population practically doubled every home game, parking was a nightmare. Thousands of people always ended up walking past our house and apparently, I saw this as an opportunity.

I went out and collected fallen maple leaves from the front yard and tried to sell them to people walking by. It didn’t make a ton of sense, as there were thousands of them all over the ground—but that didn’t stop me. If I remember correctly, a very nice woman gave me five bucks for one. Which to this day is one of the reasons I always try to stop and buy something when kids are out selling lemonade or whatever. It’s never too early to encourage creative, opportunistic thinking.

Entrepreneurship really is for everyone—even if you never officially start a business or a company. It’s a great model for identifying problems and fostering optimism about creating solutions. And the value of entrepreneurship is so much greater than the pursuit of money.

Entrepreneurship… isn’t about money? Yeah, I said it.

At least for me, that has never been the most important part of it all. There’s so much joy and learning opportunity in taking a novel idea, trying to make it work, and seeing what the world had to say about it. I imagine I’ve fostered this mentality partly due to having ADHD and being a high sensitivity person. A lot of the things that were supposed to happen a certain way in school and my career didn’t really work for me, so I’ve had to find my own ways to bring it all together.

While hustling dried leaves to captive passers-by might have been my first venture, it certainly wasn’t my last. I’ve learned continuously from my entrepreneurial explorations since then, and have found a myriad of interesting ideas. One of those ideas, is an incredibly effective model in the startup world for developing new ideas that works flawlessly in developing new habits, too.

I’ve come to call it the Minimally Viable Action, a Break the Twitch concept adapted from something called Lean Startup methodology—the Minimally Viable Product.

The Minimally Viable Product, or MVP

Ideas are great, but they’re a dime a dozen; they don’t carry much value unless we do something with them. When an entrepreneur has an idea, she needs a way to see if that idea is actually viable—without immediately raising millions of dollars or investing years of life into building the idea when it, well… might not be that great.

An MVP is a simple and inexpensive version of the entrepreneur’s idea, created to test and get feedback that will be incorporated in the next prototype. The process is iterative and evolves with each version to make small improvements along the way. The team is able to change the idea more quickly, easily, and cost-effectively based on early audience feedback. It doesn’t make sense to spend months building a feature that no one ends up wanting, right? By the end of this process she, in theory, has something that works well, and that people actually want.

A few examples of this would be:

If you have a big idea for a new type of electric car, start by applying the idea to an electric skateboard. You’ll learn if your concept for propulsion is practical, and what challenges might arise at a larger scale.

Perhaps you want to start a business in the agricultural industry, creating a new hybrid fruit by combining an orange and an apple. Driven by the deep desire to finally put all the comparisons to rest, you start looking at farms to buy to create your vision. Instead, start with an inexpensive, fast-growing fruit like raspberries or strawberries in your backyard.

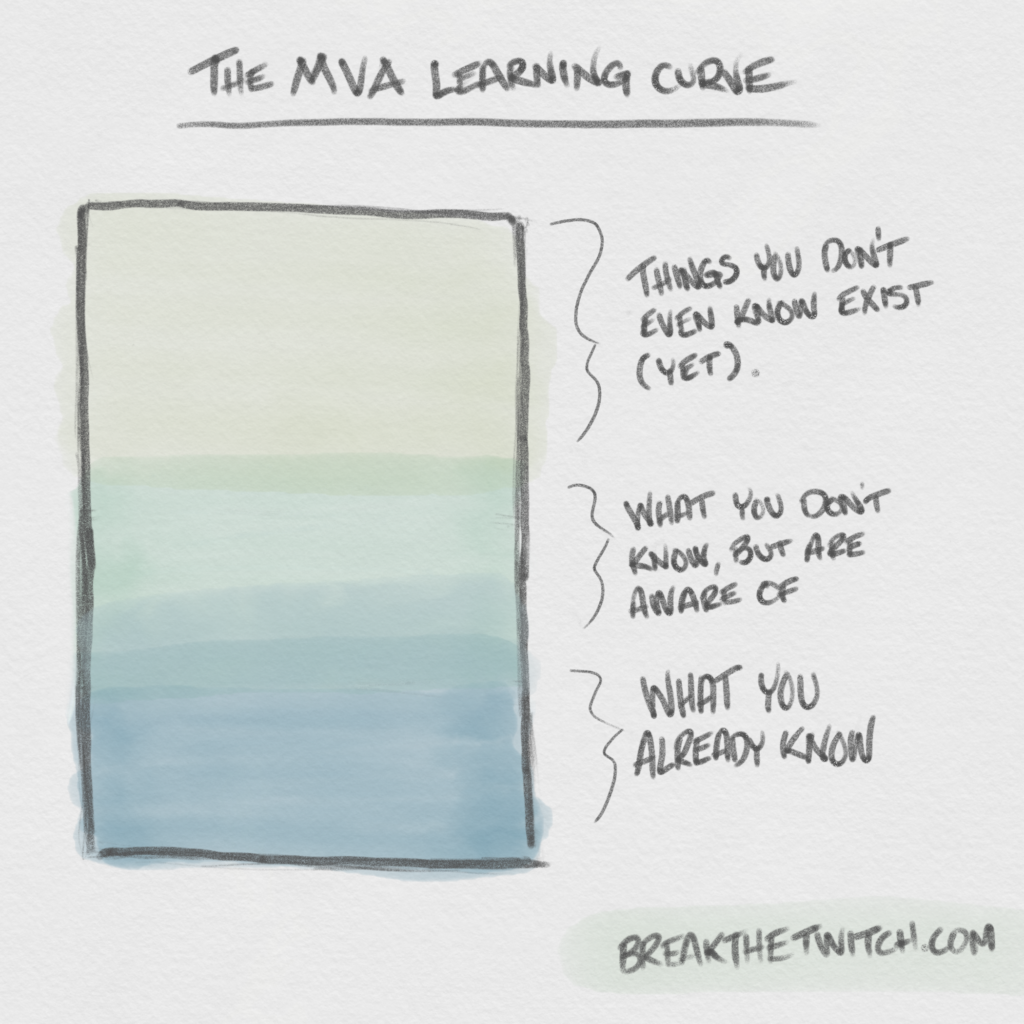

When you start any project like this, the biggest problem is not yet knowing what you don’t yet know. You can spend years theorizing about this, but it’s more effective to test the waters and learn by following the process.

New Habits Are Just Like Big Ideas

Habits tend to carry a lot of weight for people—they did for me at one point, too—but I’ve learned to put a lot less pressure on the word. To me, habits are just how we show up in our lives with regularity. They’re the little things we do consistently over long periods of time—and we’re doing them whether we intend to or not. As the years pass, they become the way we spend our lives.

If you do something for five minutes each day, you’ll look back on a lifetime of doing that thing; not any one day in particular, but a long streak of color in the blur of a life well-lived.

With life being how it is though, starting and maintaining any positive habit can feel like an incredible burden. There’s a lot of deep human psychology at work that causes this, and we all have different reasons. For me, a big part of the resistance I’ve felt is the perceived distance between where I am and where I want to be. If the initial resistance didn’t get me, the pressure I put on myself to consistently see improvement eventually would. To make it work, we need to think like an entrepreneur—both in the way we try and the way we fail. Here’s how to do that.

Introducing Minimally Viable Action, or MVA

While modern culture has conditioned us to expect quick results and overnight success, that would be like trying to design a car without any experience. There are so many variables at play, so we need to start smaller and figure out what challenges might arise.

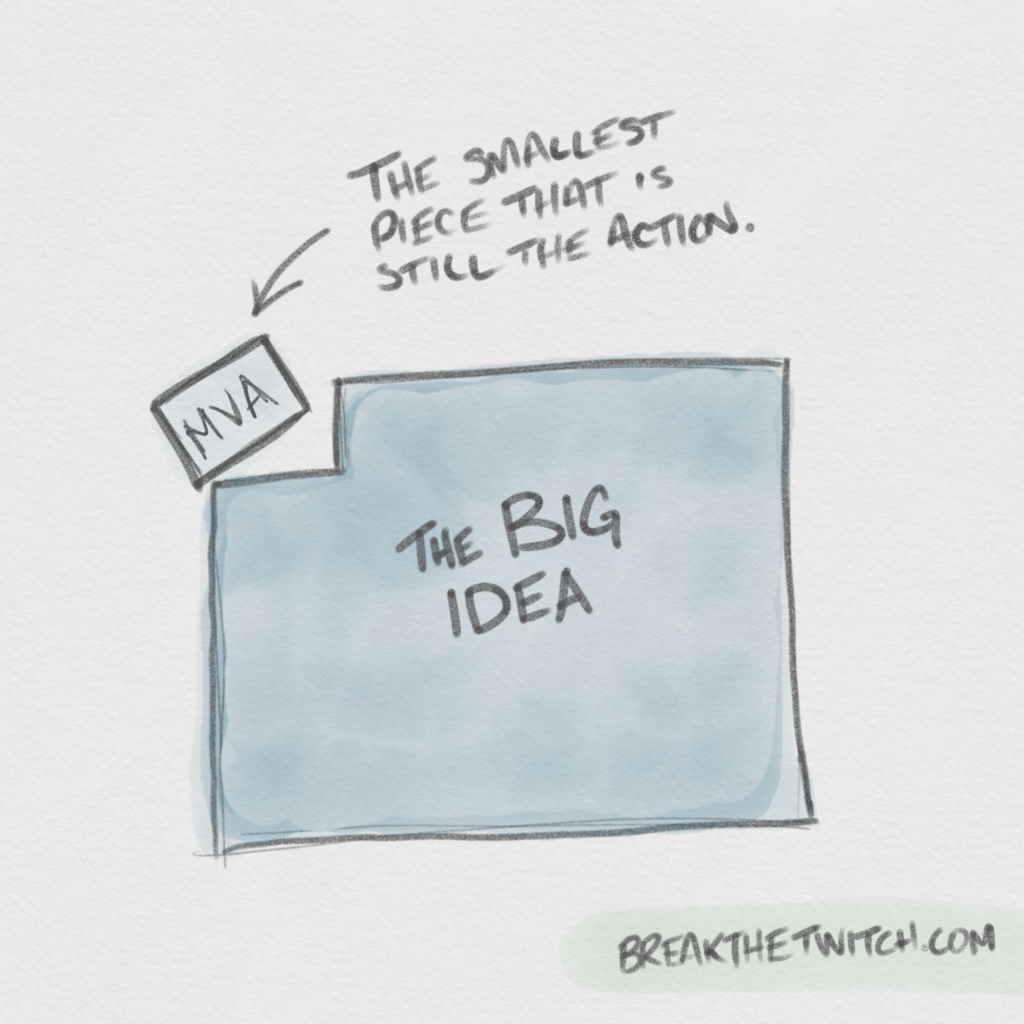

A minimally viable action is the smallest and easiest-to-do action of the habit you are trying to form.

With a Minimally Viable Action, we have the ability to test out a new habit just like it’s a simple lifestyle experiment. This allows us to see what issues come up, make adjustments, and continue on.

You don’t want mile two of a marathon to be the place where you discover that your new running shoes are rubbing in all the wrong places. That sounds terrible, and I doubt anyone would be encouraged to do another one after that experience.

To effectively use the Minimally Viable Action, you really need to boil down the new habit to its essence. Make it so incredibly simple that it becomes the easiest possible thing to do while still doing the thing you set out to do. A skateboard isn’t a car, sure—but it is a four-wheeled electric propulsion system designed to transport a human from A-to-B. If I had to design a full electric car from scratch, I would probably never bother starting because the thought is entirely overwhelming. A skateboard on the other hand? Complicated, but seems manageable, right?

By creating a minimally viable action, you’re increasing your chances of actually doing it—even when unexpected things come up during the day. It’s creating a goal with such little resistance that it’s hard not to do.

How To Build Habits That Last

1 / Create A Minimally Viable Action

The first step is to consider the new habit you want to build and break it down into a small, easy action. The most common mistake with habits is going too big, too fast and burning out or running into unforeseen problems. If the MVA you’re choosing feels silly, you’re on the right track.

For example, if your new habit is to exercise more, but you’ve been almost completely inactive lately, the MVA would be to put on your sneakers and take two steps outside. That’s it. Maybe take some breaths of fresh air while you’re out there.

If you want to eat more vegetables, the MVA would be to have a few pieces of broccoli with your lunch. The goal isn’t to do as much as you can today; it’s to have enough in the tank to still do the action tomorrow, the next day, and so on. If you stuff yourself full of veggies on day one, especially if you haven’t developed a taste for them, the last thing you’re going to want to eat the next day is vegetables.

We’re not going for results today—we’re going for paradigm shift.

2 / Test, Improve, Repeat

After you create the minimally viable action, the next phase would be to test, improve, and repeat. Just like an entrepreneur would test an MVP, you’re going to test the MVA you’ve created.

A week or two into it, you may choose to increase (or reduce) the difficulty, change some aspect of your habit, or try something else entirely! Continue to skew on the side of keeping it simple, even if you’re scaling up. This phase is all about testing and improving the MVA as you go along, so you stay consistent with the habit.

3 / Pivot!

Let’s say it’s really not working out, and something has to change. Back in entrepreneurship land, when a minimally viable product is presented to an audience and receives poor feedback, or a better opportunity appears, the entrepreneur doesn’t give up. She can always pivot and create a different solution for the same problem or use the MVP to solve a different problem entirely.

Wrigley Gum is an incredible story of pivoting: Did you know Wrigley’s Gum started as a business selling soap?

William Wrigley Jr. offered premiums as an incentive to buy his soap, such as baking powder. Later in his career, he switched to the baking powder business, in which he began offering two packages of chewing gum for each purchase of a can of baking powder. The popular premium, chewing gum, began to seem more promising, prompting another switch in product focus.

Wikipedia

Not only will you find the challenges by trying something out, but you’ll find the opportunities that come with it too!

If you realize that walks aren’t the right exercise for you because of a heel issue, perhaps riding a bike would be a better fit. If you find out that you hate steamed broccoli, try cooking it another way. Better yet, try literally any other vegetable—there are so many of them! It might just be a green protein smoothie in the morning that does the trick. Trying out different solutions will help you find something you enjoy, so the habit stays around for the long haul. When things get boring, switch it up and find something new that serves a similar purpose.

There’s really no need to be rigid in our approach to building habits that become the way we live.

When building a habit, remember everyone is different. What works for one person may not work for someone else. Remember there is always a way to stay curious and look for creative solutions along the way. Keep it up, and you’ll find what works for you, too. Even the best products and greatest ideas have a lifespan. When you get bored, get creative and find the next thing that helps you stay engaged.